- Home

- Cynthia Gael

Brass and Bone Page 6

Brass and Bone Read online

Page 6

“Oui.” I stood too and smiled my thanks. “Forgive me for keeping you.”

Simon bowed. “A pleasure.” He headed for the door.

“Simon…wait.” I ran to stop him. “I have not properly thanked you for interceding on my behalf back at the Witchfinder’s estate.” I reached up, brushed my lips against his cheek and smiled. “Thank you for being so vaillant.”

Simon seemed surprised by my actions, but he bowed once more. “Bonsoir, Cynara. And you are most welcome.”

I nodded, grateful the Fates had sent someone who would help me get through this voyage. Especially one such as Simon. He was much too easy to talk with. Share the time with. A kindred soul, if you will.

I would have to be very careful around him and not share too much regarding my ever-growing plans to kill Henri. Though considering Henri’s reaction tonight regarding my inheritance, perhaps allowing dear Henri to become a pauper would be the best revenge possible.

If only my heart would allow it.

Chapter Four

Simon

It was early, far earlier than I liked to rise. I could not suppress a yawn as I made my way down the untidy pathway and through a small copse. Out of the trees, I blew on my chilled hands as I headed in the direction of the field where Abigail kept her grandfather’s old airship, nestled away in a rat-infested hanger that had begun life as a smuggler’s barn. The barn had tunnels connecting to Bartleby, which had made it convenient for hiding from George’s excise men back in the last century. The tunnels were still useful—her dear grandpapa had been quite the smuggler himself until his untimely demise at the ripe age of eighty-nine. He had no compunctions about breaking the law, a trait he passed down to my dear Abigail.

I mounted a small rise, too little to be called a hill, and came upon a scene of ultimate and utter confusion. The wide double barn doors were open, and the airship gondola just inside had men swarming over it, making it resemble a ragged hornet’s nest. The series of airbags were spread on the field beside the barn, and there were quite a dozen men and women working on the material, repairing tears and adding patches, enormous needles flashing in the sun. All in all, there must have been upwards of thirty people employed in making the shaky old thing airworthy again.

I’ll give him this—Sir Eli does not stint when it comes to his own affairs.

I made my way to the open doors, dodging workmen loaded down with tools and equipment. Just inside, Rupert presided over a battered old table with a tea urn and plates of sandwiches.

“Where is her ladyship?” I asked him as I dodged two men carrying a long wooden beam who looked intent on decapitating me.

Rupert, smiling at a black-haired woman whose apron bristled with needles as long as my hand—obviously a seamstress working on the airbags—barely spared me a glance. “She’s in the engine compartment, Mr. Simon,” he said as he poured steaming tea into a series of mugs. “She and three of Sir Eli’s engineers are in deep in conversation about…something.” He waved toward the back of the huge barn before holding out a plate of sandwiches to the buxom wench, who simpered and took four.

I could see Rupert had his hands full, so I edged my careful way past the gondola to the rear of the barn. There I saw, encased in wide straps and hanging from a beam far overhead, what I assumed to be the airship engine. Or at least some greasy, dirty mass of iron and brass, with bits sticking out in what looked like no sort of rhyme or reason.

I confess it, here and now, something you may have already suspected: I am not mechanical. All that I leave to Abigail. My talents are elsewhere.

Off to one side of the hanging mass several men sat, using bales of hay as a table and with sheets of paper spread out before them, murmuring among themselves. But I could not see Abigail, which surprised me. Ordinarily, in matters of this sort, she would be in the middle of things, covered in grease and reeking of oil, happy as a clam.

“Your pardon,” I said to the murmuring men, “but can you tell me where Lady Abigail might be?”

“Simon, you old slacker,” came the most familiar voice I know. “Finally decide to crawl out of bed, did you?”

Since by my pocket watch it lacked several minutes of seven in the morning, I did not deign to reply. Instead, I tried to find where her voice was coming from. With Abigail, one never knows. I once discovered her in the bottom of one of those massive holes near Baker Street where they’re putting in the underground trains; she was having tea with a pair of Irish navvies.

But this time I could not see her, though her usual tuneless humming echoed throughout the barn. She was happy, I could tell by the humming, but she was invisible.

Finally, I could stand it no longer. “Abigail, where in the name of all that’s holy are you?”

A sort of trembling went through the mass of sticky, greasy metal hanging from its half-dozen straps, each quite as wide as my waist. Then a hatch popped open at the very bottom and swung free. An instant later a face appeared in the hatchway, upside down, covered in filth, dripping with sweat, and grinning with the kind of joy I, for one, only feel when contemplating a new waistcoat.

“Abigail, what are you doing inside that…that…thing?” I asked in some concern as I hurried over. “Get out at once, do you hear me?”

Of course, she did not get out; she simply laughed and disappeared like a jack-in-the-box wound in reverse. Her disembodied voice boomed from inside the thing: “Never fear, Simon old thing. Eli has sent me some rather tasty new additions to Grandpapa’s engines. I’m just installing them with Herr Tesla’s assistance.”

“Wait a minute!” I called, looking for something to bang on the thing with—I was not going to dirty my hands unless it was a matter of life and death. “There’s another person in there with you?”

“Two others, actually, sir,” said one of the gentlemen who was previously at the hay-bale table. He’d appeared beside me, a small grey metal device about the dimensions of a cigar box in one hand. He took a spanner from his overall pocket and tapped on the side of the engine.

The hatch reopened, and Abigail’s oddly inverted face reappeared. “Ah, the power source. Thank you, Smithers.” She grabbed the device, disappeared, and I could hear more sounds inside. I shall not describe them; a lady may be reading this.

Finally, the hatch opened a third time. Abigail slithered out in the boneless way she has. She wiped her filthy hands on her filthier coverall and nodded at me, her grin still firmly in place. “You will be delighted to know,” she began to me, and I prepared myself for a lecture, “that Sir Eli has provided us with an experimental and quite amazing new power source. Oh, never fear. It is quite safe, and we’ll still carry coal for the boilers in case of emergencies. But if it works as Herr Tesla assures me it will, we shan’t have to stop for refueling nearly so often. And our speed, Simon! Our speed!”

Then she went off into one of those mathematical fugue states I cannot imagine ever being able to comprehend, something about trajectories and azimuths and, for all I knew, processions of the equinox—or is it Esquimaux? Still, I nodded and looked as if I understood until she ran down at last.

In the meantime, her two companions inside the engine had also clambered out, neither of them with near her grace, and stood conferring with the one who’d handed in the grey box. Herr Tesla, his hair standing up all over his head as if he’d been standing on a generator, came over to us. He was not nearly as dirty as Abigail, but he looked almost as happy.

“There now, we shall see how this lodestone device works, Lady Abigail,” he said. “It is most kind of you to help us with the prototype. You have all my thanks.” He took her hand and bowed over it in the sort of European way I found so irritating.

Then I realized what he’d just said. “Wait a minute! Does ‘prototype’ mean what I think it means?” I asked with more than a little uneasiness.

Abigail reached to pat me on the shoulder, but I dodged out of the way of her greasy hand. “Now, not to worry. We have all our usual equipment

. We’re just helping Herr Tesla here with a few tests, that’s all. Keep calm, my dear fellow, and leave everything to me.”

Well, I ask you. How could I do anything else? We were in this, as in all things, together.

But I did not have to like it.

Then something occurred to me. “Um, Abigail? I’ve told Mademoiselle des Jardin you plan to leave early tomorrow morning, and now I find your old airship in a dozen pieces. Shall I tell her we’ve had a change of plans?” Even to me, my voice sounded hopeful.

“Not in the least,” Abigail said. “We’re done with the modifications, the engine will be installed shortly, the airbags are nearly done, and I’ll take her up for a test flight this afternoon before tea time. Now run along, there’s a good boy—I’ve got work to do.”

I hated it when Abigail spoke to me like that, as you can no doubt imagine. I blamed it on the fact I was a child when we met, and I often suspected she saw me as little more than a ragged urchin still. One day I would impress her; so at least was my vow.

But until that glorious day, I felt my best plan was to do as she asked—get out of her way.

***

The tests went admirably, so Abigail told us at tea, so well in fact she’d actually had time to bathe and change her clothes, thank the Lord.

“So we leave in the morning as planned, I take it?” asked Monsieur d’Estes. “Well done, Lady Abigail, well done indeed.” And the cad smiled at her like she was a dish of Devonshire cream and he a hungry cat.

“Thank Sir Eli and Herr Tesla,” Abigail said then took a bite of one of Rupert’s delectable cakes. “His people are loading supplies into the Invincible now. And such supplies! Grandpapa would be delighted, I must say. I need to take her up for one final test flight with Herr Tesla to give me a bit more information on his power device. Then I’ll moor her down at the old dock on the shore and, with luck, we’ll leave at dawn. Rupert?”

“M’lady?” Rupert handed Mademoiselle Cynara her cup then turned an attentive look to Abigail.

“Will you make certain all our personal luggage is loaded before supper? I won’t bore you all with weights and such,” she cast me a meaningful grin, “but those things are important with an airship. I’ve taken the liberty of having all your luggage weighed and measured, and Rupert bows to no man in his uncanny ability to stow things away in the most orderly fashion.”

“Lady Abigail, can you tell me something more of what to expect in this long journey, s’il vous plait?” Mademoiselle des Jardin smiled prettily and accepted a scone from Rupert, who seemed intent on dazzling her with his cooking. “I have ridden the airships on the Paris-to-London route, but nothing any smaller. Will we eat and sleep aboard? Do we set down in towns along the way? What is our itinerary, if I may ask?”

“Surely, my dear, the baggage does not deserve to ask the captain how it will be transported,” d’Estes said with a sneer.

I hadn’t liked him before. You can imagine how little my opinion improved at this remark. I prepared to leap to the lady’s defense.

But my darling Abigail was quicker. She set her cup down with a clatter, bolted straight up out of her chair and turned to d’Estes, her grey eyes like storm clouds. “Monsieur, we are going on a very long journey together. I consider you and Mademoiselle des Jardin my passengers. Allow me to inform you now that you are both subject to my orders, and we shall all behave as civilized beings throughout. If you do not do so, then let me point you to the British Navy’s Article four-oh-seven, which pertains to the duties, responsibilities and power of a captain when at sea or in the air. You will find I should be quite within my rights to have you put in irons if I feel you are a danger to my ship, my crew or my passengers.”

“Or removed from the ship, I believe, if I recall the article in question correctly,” I could not help but interject. Personally, I would prefer to remove him at an altitude of somewhere around a thousand feet.

“Quite right, Simon.” Abigail nodded. “Now, monsieur. Are we clear on this matter?”

Henri d’Estes rose. I suspect he wanted to tower over Abigail in an attempt to intimidate her. I could have told him that would be far more difficult than, let us say intimidating the Nile into changing direction or the hurricane into ceasing to blow.

In other words, quite impossible.

But the Frenchie surprised me. The bounder saw intimidation would never work and changed his tactics at once. He fell to his knees before Abigail, seized her hand and kissed it humbly. “My deepest apologies, Captain Moran. In the words of your estimable queen, ‘I will be good.’”

I, for one, did not believe him.

And I suspected by the look on the mademoiselle’s face she did not either.

***

The old Invincible had never looked better, even in the ungodly hour of half-past dawn, as she tugged gently at her moorings down on the beach.

I’d had the pleasure of escorting Mademoiselle des Jardin onboard, and she insisted again I call her Cynara. What could I do, after all, but ask her to call me Simon?

“Careful, Simon,” Abigail said when I’d taken Cynara to her doghouse of a cabin. “I believe the lady has a tendresse for you.”

I fear I blushed. I certainly changed the subject.

Herr Tesla himself was there to cast off our lines, and the ragged old airship, Abigail’s pride and joy, rose majestically into the blue of morning, setting her course for Paris.

We were on the bridge, surrounded by a gleaming mass of utterly indecipherable—at least, to me—gauges and displays and knobs and wheels and such, plus a narrow bunk and a wicker chair which had seen better days, and those in the last century. I’d sought Abigail out for a quiet word. Actually, I’d been trying to corner her for a talk ever since we’d left Sir Eli’s manor, but she’d been surrounded and madly busy. Now we were underway, the others settling into their cabins, Rupert brewing tea over a spirit lamp in the minute galley in the stern, and I at last had the opportunity for a quiet tête-à-tête.

“Abigail,” I began, “I know how much this old ship means to you. But are you quite sure we’re doing the right thing? I mean, after all, a jaunt halfway around the world to deliver a metal box that locks with blood? Have you ever heard anything so penny-dreadful in all your days? This Sir Eli…I could not help but notice he was somewhat the worse for drink, and I suspect more than a little mad. Perhaps we should simply release the lady and gentleman in their native country and sail or cruise away, or whatever the correct term is, and make our fortunes somewhere else. What do you say?” I was warming to my own idea now. “Imagine it.” I waved out the front glass to the billowing waves below. “Sailing across the world, visiting spots of interest, dropping down for a bit of skullduggery now and again just to keep our hands in things—”

“—And always on the run from the minions of WFG, hunted for our lives, danger at every turn,” Abigail finished. She turned away from whatever she was doing and took my hand. “As exciting and pleasant as that sounds, dear boy, I have given my word. Eli is an old and very dear friend, and he wants this thing done badly. I owe him now for my rejuvenated airship and for other…things. I’m sorry you feel this way. Perhaps you’d like me to leave you in Paris? We’ve got more than a bit of the ready, old thing, and you could have quite a shopping spree until I get back from the Antipodes.”

I was, of course, aghast. “Of course I shan’t let you go without me! We’re a team, partners, together through thick and thin. But I simply wanted to point out—”

Something dinged, or possibly donged, and she turned away to flip a lever up two notches. Ahead through the glass—it had been replaced with Sir Eli’s money and was quite crystal clear in comparison to the cloudy, cracked old wreck it had been—I could see spread out below me the bustling port of Calais, looking quite impossibly French.

Then Abigail started doing other things, and bells rang and whistles whistled and I could see we were changing direction. So I turned to leave.

It was use

less, I could see. Whatever feelings Abigail had for Sir Eli were still there. A pity.

“Simon,” Abigail said just before I left the bridge. “The distance from Calais to Paris is just shy of a hundred fifty miles. We’re traveling at nearly—,” she looked at a gauge and whistled in delight, “—at over twenty-five miles an hour. Really, I must send a congratulatory telegram to Herr Tesla once we arrive. Tell our passengers we shall be in Paris for a late lunch.”

***

Ah, Paris! The city of light, the center of the world—at least, if one is a Frenchman.

As for me, give me dear old London. It may be foggy and rather soiled; there may be dangers at every turn; I may get lost upon occasion in its cluttered streets, or attacked by cutpurses or solicited by ladies of the evening or…

Well, perhaps I should give Paris a chance.

I spent the forenoon hours settling into my minuscule cabin, and if the thought of living there for some time to come as we traveled was less than inviting, well, who can blame me?

Perhaps this might be a good time to describe the Invincible, so you may visualize it when I discuss such aeronautical locations as the bridge, engine room, galley, hold and so forth. It had begun its life some fifty years before, when the first airships were built. It consists of a long gondola suspended beneath the airbags, which are nothing more than a series of five large round sacks filled with hot air produced by the engines below. The gondola, shaped much like a stocky sailing galleon, has three levels: the upper deck, which is little more than an open walkway upon either side of the glass-enclosed bridge wherein Abigail spends most of her time, with her small cabin behind it; the second or passenger deck, with three tiny cabins on each side of a central corridor and a small galley aft with a cubbyhole where Rupert holds sway; and below, the third deck is one long open hold, used in the past for the contraband so dear to the late Lord Agamemnon Moran, Abigail’s grandpapa and a most impressive old pirate and smuggler. The hold is also wherein resides the airship engine, lately modified by Herr Tesla. The gondola is made of wood and metal and hangs beneath the gasbags, which are sewn of heavy waxed canvas and bound to the gondola with stout ropes.

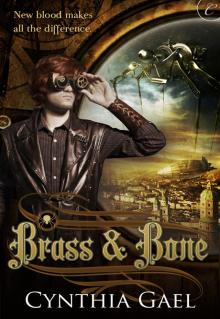

Brass and Bone

Brass and Bone